Ample Land Drew German Settlers to Loudoun County

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

The first Germans, a group of 42, came to the Virginia Piedmont in 1714 to work in Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood's iron mines in what is now Spotsylvania County. Their settlement was known as Germanna, and as it grew, residents left to form other communities, in Germantown in Fauquier County in 1719, in present-day Madison County by 1725 and in the Little Fork area of present-day Culpeper County in 1728.

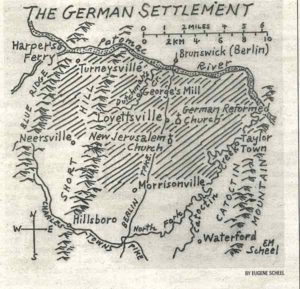

The largest group, however, did not emanate from Spotwood's colony but came to northwest Loudoun County from Pennsylvania. They founded what was called the German Settlement and became the town of Lovettsville. Questions remain about when they arrived.

The Lovettsville Historical Society Museum said the first German families arrived in 1732. Many publications, however, have quoted historian Briscoe Goodhart, a descendant of the early Germans, who wrote in an 1896 Loudoun Telephone newspaper article, "The German Settlement," that Germans came to the county in 1727 and in greater numbers in 1734.

Marty Hiatt, a genealogist who has studied the Loudoun Germans and their migrations for 14 years and has lived in the German Settlement most of that time, said "there may have been a few [Germans] here in the 1730s, but there were very few."

Whatever the date, there is agreement that the Germans who moved to Loudoun came from Pennsylvania and the Palatinate, an 18th-century state of the old German Empire.

Hiatt said many Germans were attracted by available land in Loudoun. She said that when William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania, died in 1718, his land holdings went to his grandchildren, who could not sell them because they were minors. Much of the other good land in Pennsylvania's Lancaster and York counties was already taken, and much of the land in Maryland had been settled. Much of the land south of the Potomac River was forest or scrub.

There were property owners, however, chief among them William Fairfax, who had the land south of the Potomac surveyed in 1736 and divided into two manors, or estates, for himself and the Fairfax family. The manors, which totaled about 47,000 acres, were called Shannondale and Piedmont. Fairfax was the land agent -- today we would call him a real estate agent -- for Thomas 6th Lord Fairfax, his first cousin.

Today, Shannondale Manor is the valley between the Blue Ridge and Short Hill mountains, known as Between the Hills. The Piedmont is the region approximately between Catoctin Creek and Short Hill. To the east of Piedmont Manor, John Colvill, a Tidewater land speculator, amassed a 16,000-acre manor called Catoctin, with William Fairfax's consent. This manor extended east to Catoctin Mountain.

Land in these manors would be leased, not sold, so the rents would provide income for the Fairfax and Colvill families.

Three snippets of evidence indicate that some Germans may have lived in these manors even before 1732. A 4,063-acre land grant to speculator Francis Awbrey in 1731 mentions "Dutchman's Creek," a tributary of the Potomac. Early Germans were often called "Dutchmen" -- for "Deutscher Man." The southerly boundary of that grant coincides with today's Broad Way, the main street in Lovettsville.

Second, a 1734 letter from William Fairfax to Bryan Fairfax, a cousin and adviser to Lord Fairfax, said that Lord Fairfax's upper Potomac River boundary was not being "properly ascertained" and that "sundry families from Pennsylvania" were living on land that had not been leased to them by Lord Fairfax.

The sundry families could have been 16 German families from Pennsylvania who began settling in the lower Shenandoah Valley in 1732. Their leader, Joist Hite, had received a grant from Lord Fairfax to settle the families on Fairfax lands west of the Blue Ridge and Shenandoah River. At the time, William Fairfax was living in Westmoreland County, far from the valley and the German Settlement.

The third piece of evidence is another 1731 Awbrey deed to land at the Potomac River and "at the Blue Ridge at a place called the Meeting House." In Colonial times, a meeting house usually meant a house of worship, but in this instance it could have been a private home where families worshipped. Today, this meeting house would be in the vicinity of the village of Turneysville, in the far northwest corner of Loudoun.

Rather than protesting these German squatters, William Fairfax and Colvill welcomed them, for they were improving the land. No leases have yet surfaced to tell of any financial or crop-sharing arrangements between Fairfax and Colvill and their presumed renters. Whether written or oral, these presumed leases would, in most cases, be in effect for more than a half-century.

There is evidence that a German man, Elder William Wenner, lived in future Loudoun in 1748. The diary of the Rev. Michael Schlatter, a German Reformed minister from Philadelphia, mentions being hosted by "a pious Elder of the Reformed Congregation living near the Potomac River opposite Berlin" -- today's Brunswick.

Eleven years elapse before there is proof of other Germans living in Loudoun. The proof comes from a tithable list, which is undated but presumed to have been compiled in 1759, two years after the county was created, according to Louisa Hutchison, a researcher of early Loudoun records. The census taker was Josias Clapham, who lived at present-day Chestnut Hill, on the eastern fringe of the German Settlement. He listed 30 to 35 heads of families who had names of probable German derivation.

Tithables, as they were know in Colonial times, were people who paid taxes to the Anglican parish where they lived, which in this instance was Cameron Parish and, after May 1770, Shelburne Parish. Their tithes went largely to support the indigent and infirm. Tithables were everyone 16 and older, except white women. After 1786, when the Anglican Church in Virginia was officially disestablished, tithes were no longer demanded of state residents.

As families were large in Colonial times, there may have been more than 150 people of German origin living in Loudoun in 1759.

A three-volume series, "Loudoun County Virginia Tithables, 1758-1786," compiled by Hiatt and genealogist Craig Roberts Scott, invites ready comparisons. In 1761, the number of Germanic-sounding names increases to about 45. The 1785 list -- the last available for the German Settlement -- has 67 German families, 10 with the surname Shoemaker or Shumaker.

These families lived, for the most part, in what were called "mean" houses in Colonial times, meaning small or unassuming. Before the 1980s, when renovations and additions began to alter the Germans' original dwellings, their settlement, especially west of the Berlin Turnpike, was dotted with small log and frame structures, complete with large stone center and end chimneys.

In his 1853 "Memoir of Loudon," Loudoun chronicler and mapmaker Yardley Taylor described their farmsteads as "generally small and well cultivated, and land rates [of crop yield] high, This class of population seldom goes to much expense in building houses. . . . Many old log homes that are barely tolerable, are in use by persons abundantly able to build better ones."

Goodhart, in his essay "The German Settlement," emphasized that many family's forebears and friends were blacksmiths, carpenters, shoemakers, weavers and others who worked with their hands. "This array of artisans made the colony strong, independent and self sustaining, from the very beginning," Goodhart wrote.

He had special words for the "fair daughters [who] were experts with the wheel -- not bicycle, but spinning wheel, and supplied yarn for stockings, and with the loom made blankets for bedding and woolens for winter clothing."

Goodhart added: "The forest was rapidly cleared and generally one-room cabins were erected and a system of small farming inaugurated at once. The first sheep were brought to the County by these settlers. . . . Everything pertaining to farming was primitive. Iron was scarce and very expensive. Nearly everything was made of wood."

The small farms cited by Taylor and Goodhart -- farms that in some instances might have been rented since the early 1730s -- were designated by size and location in leases filed in Loudoun land records during the 1770s and '80s.

An intense period of leasing took place from March 1786 to June 1787. In those 15 months, I counted 86 leases in the former Piedmont and Shannondale manors from George William Fairfax, William Fairfax's eldest son, to people with German-sounding names. The farms ranged from 40 to 240 acres, averaging about 100 acres, which was small for that day, considering that Quaker spreads to the south averaged more than 300 acres.

The 240 acres were leased by John George, who had built a mill on the holding. The village of George's Mill soon grew up around the mill, and today the farm and village remains in the family as George's Mill Farm & Stables and includes a bed-and-breakfast.

In preparing the leases, George William Fairfax was careful to specify that the properties would have to be improved and that if rents were not paid, the land would revert to him. For instance, the lease to John George specified that he should "plant upon the Demised Premises one Hundred good Apple Trees and two Hundred Peach Trees at least thirty feet Distance from each other, and the same will enclose with a good sufficient and Lawfull fence, and keep them all well pruned; and that he [John George] and they [his family] shall and will Erect and Build a good Dwelling house twenty feet by sixteen, and a Barn twenty feet square, after the manner of Virginia Building."

In his lease to George, and to the other lessees of the Piedmont and Shannondale manors, George William Fairfax reserved the sole right to "all mines, Minerals and quarries whatsoever, and the use of them, and the privilege of hunting or fowling on any part thereof."

As generations of Germans passed, so, too, did the German language in their two houses of worship on the skirts of Lovettsville. Vernacular services at the Lutherans' venerable New Jerusalem Church, which was founded in 1765, ended in 1845.

At the German Reformed Church from 1811 to 1823, minutes alternate between German and English. The last minutes in German date from August 1823, and in June 1831, the church's constitution was translated to English from the "German language which many of the younger members cannot read."

With the disappearance of the language, the Fairfax name, once indelibly linked with the Germans' history, also became forgotten. It had "dissipated like the smoke of their ancestors' chimneys," historian Fairfax Harrison wrote in his 1924 epic, "Landmarks of Old Prince William."