Purcellville: A Place Where Everyone Knew Its Nicknames

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

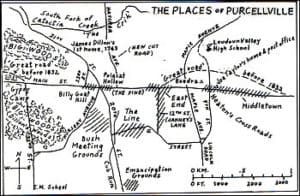

Purcellville was incorporated as a town 100 years ago, but the village existed in the early 1800s. Because it had no street signs then, nicknames were used. (Courtesy of Eugene Scheel)

Here is the history of Purcellville's old and mostly bygone nicknames for the town's streets and neighborhoods.

Although Purcellville was incorporated as a town 100 years ago, the village dates to 1822, when its post office, named Purcell's Store, opened. No street or directional signs of any sort existed until more than a century later, so nicknames were vital as a means of identifying places.

Sewertown is the first nickname of record. It was a byword for the entire village and was noted as the return address on an 1849 letter.

The village's center was a low spot known as Polecat Hollow, now Main Street and Nursery Avenue. Polecat is a common rural name for a skunk, and the hollow was 10 feet lower than the land around it. Brothers Asa Moore Janney and Werner Janney, in their book "A Medieval Virginia Town" called the hollow "as muddy and rutted a piece of public way as you could ever hope not to meet in a town." The mire was the repository for animal waste until Main Street was paved in 1927.

Today, a floral display and an American flag occupy the spot. The American Legion maintains the area as a memorial to U.S. veterans.

Main Street, officially the Leesburg and Snickers Gap Turnpike until tolls were removed in 1921, was known as the Pike through the 1950s.

The Pike ascended west of Polecat Hollow, and the rise -- not as noticeable after the street was paved -- was termed Billy Goat Hill. The animal, a good climber, was known to village residents as the cropper of lawns and lots.

West of Billy Goat Hill were vast forests known as the Big Woods and in the early 1800s as Dillon's Woods. The 1763 home of James Dillon, Purcellville's first known resident, bordered this hinterland, and subsequent Dillons cleared it. A portable steam-powered sawmill owned by prominent Purcellville businessman Nick Hampton began felling the woods in 1901.

The Gypsy Camp was the main feature of the Big Woods from late fall to early spring. It was populated by southern European immigrants who lived in northern U.S. cities the rest of the year and went to Purcellville for its milder winter. The camp stood by the Pike from the 1880s to the mid-1930s on what is now the Loudoun Golf and Country Club.

"Their wagons and harnesses were brightly colored, usually black and red," recalled Allin Tibbs, who was 106 when I interviewed him in 1977. "By spring, there'd be a mudhole of [horse] manure, enough to cover a 40-acre field. Gypsy men liked to stay home and gamble; the women went off to beg and tell fortunes. Once a year, at Christmastime, Gypsy bands from all over would come together."

The East End of Purcellville was called just that. The timber from Hampton's sawmill was used to frame houses there at the turn of the 20th century.

The houses on Janney's Lane, which was named for family members who owned remnants of Amos Janney's 1741 land grant, also were the recipients of Big Woods lumber. Today the lane is 12th Street.

The intersection of Main and Ninth streets was known as Heaton's Cross Roads. Near the northwest corner stood Exedra, the grandest of area houses, built for physician James Heaton about 1804. It became the home of three generations of Heaton doctors.

Exedra is classical Greek for "sitting place," which was an apt name, relative Henry Heaton told me years ago. "It was large and livable, where locals met and discussed politics, Dr. Heaton using his persuasive powers to convert them to be Jeffersonian Democrats," he said.

Like too many of Purcellville's older homes, Exedra was crushed by bulldozers in 1966 to make way for commercial development.

East of the crossroads, people called the area along the Pike Middletown, referring to its location between downtown Purcellville and Hamilton. Because Rodney Purcell was Purcellville's Confederate postmaster during the Civil War, the post office did not reopen after the conflict. From 1867 to 1874, staunch Unionist and Quaker shoemaker Joe Taylor ran the Purcellville post office from his shop in Middletown.

Taylor's humble frame house with stone and brick chimney met the same fate as Exedra, although about 20 years later.

Within sight of Polecat Hollow was the Bush Meeting Grounds, now the town baseball field and skating rink. From 1877 to 1931, Bush Meeting was Piedmont Virginia's largest annual cultural and spiritual gathering, a week of concerts, speeches and sermons imploring a Christian lifestyle and abstinence from drinking what were then known as "ardent spirits." The August gala, named for the brush arbor that first shielded onlookers, attracted thousands. The Great Depression ended Bush Meeting.

The Emancipation Grounds to the south was the African American counterpart to the white people's Bush Meeting. The 1909 charter of the Loudoun County Emancipation Association stated that its purpose was to unify, educate and promote character and material well-being. Emancipation Day galas were held there Sept. 22, or the closest weekend day to it, from 1910 to 1967. The grounds' baseball field hosted black teams from miles around and was the playground for black youngsters.

In her history of the Emancipation Association, "In the Watchfires," Elaine E. Thompson tells of the organization's demise: "The 1960s civil rights movement captured the interest of everybody. People did not want to look back."

Buildings on the property were decaying by the 1960s, and in 1971, association stockholders voted to sell the site. Today, the only evidence of the complex is some repaired entrance stonework and a marker unveiled Sept. 22, 2000.

Bordering the Emancipation Grounds was the Line, now G Street, meaning the color line. A few African American families lived there before 1908. The nickname was known to black and white residents, but black residents would often call the settlement Cub Run, for a drain of the North Fork of Goose Creek. In the run, residents washed clothes and cooled drinks. Through the 1930s, the neighborhood expanded southward.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel