Slave Quarters - A Reminder of Bygone Era

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Anyone interested in joining or helping Friends of the Slave Quarters

should contact

A stone building southeast of Arcola proffered to the county by the Swiss developer Hazout S.A. and a pair of log structures between Waterford and Wheatland are rare examples of former slave quarters in Virginia, as most such buildings have been destroyed.

The stone building is within sight of Arcola, a village known before the Civil War as Springfield, or Gum Spring. Hundreds of slaves once lived nearby. The five-room structure was built on a slope near a small tributary of Broad Run. Each room had a fireplace. The building is unusual for its elongated shape, 17 by 63 feet, and because it is one of only a few stone structures in eastern Loudoun County.

Thomas 6th Lord Fairfax granted the 1,750 acres on which the slave quarters now stand to Anthony Russell, a prosperous planter, justice and parish vestryman, in 1728. Russell sold the land in 1748 to Vincent Lewis, another well-to-do planter.

A 1749 tithable list for Cameron Parish -- then the same area as the combined counties of Loudoun and Fairfax -- indicates that slaves might have lived on the property during Colonial times. The list shows that Russell owned four slaves and Lewis had three. All men and women who were black or of mixed race had to pay tithes, although owners had to pay the taxes for their slaves.

Historian Wynne C. Saffer lives near the slave quarters. When he discovered in the 1990s that his great-great grandparents, William and Susan Saffer, owned slaves in the area, he began researching the history of the slave quarters and its occupants.

He found that by 1796, Lewis's three sons, Charles, John and James, owned about half of the 1,750 acres. The tracts were contiguous, with the slave quarters on Charles Lewis's land, a few hundred feet from the property line of his brother, James Lewis.

Vincent Lewis's grandson, Joseph Lewis Jr., grew up on one of these tracts and represented Loudoun County in the U.S. Congress from 1803 to 1817. He also served four terms in the Virginia General Assembly, 1799-1803 and 1817-18.

As Saffer was completing his research, people interested in preserving the slave quarters and learning more about its residents and owners formed the Friends of the Slave Quarters, which became a nonprofit corporation in 2001. Saffer was a charter member, as was Arlean Hill of Chaptico, Md., who knew that some of her ancestors had been slaves in Fairfax and Loudoun counties.

Comparing genealogies, Hill discovered that her great-great aunt, Victoria Brooks, was owned by Saffer's great-great grandmother. She lived just south of the Lewis tracts.

"I was kind of fascinated," Hill said of the discovery. "You [meaning Wynne Saffer] can't be responsible for something you didn't do."

Saffer said, "The actions of some of your ancestors are things you can't control. You're separated from it."

By checking wills and censuses from 1820 to 1860, Saffer determined that the various Lewises and their children owned 50 or more slaves each census year, more than most slave owners in eastern Loudoun.

Charles Lewis died in 1843, and as he had no children, he willed his slaves to the children of his late brother James. An inventory for Charles Lewis's estate revealed a genealogists' dream. The person who prepared the inventory identified all of his 31 slaves and gave both first and last names for 22 of them. Nine slaves had the surname Simms, five were named Henderson, three were named Turner, two were named Newman and there was one each named Hogan, Owings and Sprawling.

Saffer continued his research at the courthouse archives, where he met John and Joan Kelly of Rockville, who were looking for ancestral links in Northern Virginia. Saffer told the Kellys they should contact Hill, who was still searching for her ancestors and others who might have been interred at the Arcola slave quarters.

In autumn 2001, the Kellys and Hill all happened to be at the Thomas Balch Library in Leesburg and Saffer introduced them. In comparing genealogies, Hill discovered that she and Joan Kelly were related. Joan Kelly's maiden name was Newman, and some Newmans married some Brookses at the turn of the last century. The Newmans were the same family that had lived in the slave quarters. Furthermore, Joan Kelly's research had established that the Newman line was related to the Hendersons and Turners who also lived at the quarters. The Kellys then joined Friends of the Slave Quarters.

It had taken more than a half-decade, but present-day descendants of 11 slaves living at the slave quarters in 1843 had been found, as well as links to other slave families and their owners who lived nearby.

Unable to farm profitably without slaves after the Civil War, James Lewis's family sold their land by 1884. Being stone, and used for storage of farm equipment, the quarters have survived in reasonably fine condition. Hazout boarded up the windows and doorways last year, but when I observed the structure two weeks ago I could see there were interior structural problems. The east wall caved inward, the north wall bulged and the roof sagged.

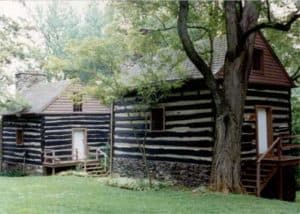

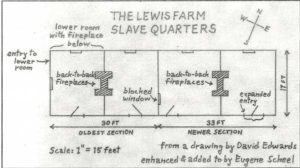

The slave quarters at Trevor Hill, a former plantation two miles west of Waterford, are significant because they are a pair, very few of which remain. During the slavery era, the 300-acre plantation was owned by a father and then a son, both named Sanford Ramey.

Ramey Sr. purchased the property in 1803 from Ferdinando Fairfax, a great-nephew of William Fairfax. The tract, with the deed implying that a tenement stood on the acreage, had been part of William Fairfax's vast Piedmont manor, granted to him by his cousin, Thomas 6th Lord Fairfax, in 1736.

Before the Trevor Hill slave quarters were built, slaves might have farmed the land. William Fairfax owned seven slaves who lived in Loudoun in 1749, and there was a house on the land in 1803. I have not been able to find a record of Jefferson County resident Ferdinando Fairfax's slaves.

Ramey, a farmer and owner of a store attached to his house, was one of a few Loudoun homeowners who insured their residences in the early 1800s, and an 1825 Mutual Assurance Society of Richmond policy is the first to indicate Ramey's slave quarters were standing, and that they were apparently the same quarters that stand today.

Outbuildings were rarely insured, but the policy covered the slave quarters and adjacent frame ice house and brick smokehouse, as well as the log "Big House," the slaves' traditional name for their owner's home. In 1976, architectural historian John Lewis called the foursome, along with the now destroyed outbuildings at the Exeter plantation in Leesburg, the finest surviving dependencies in Loudoun County.

The buildings were constructed on a line, with their fronts also facing the same direction. Each building is 16 by 20 feet and has three rooms, one above the other. The upper room with a fireplace has access to the loft. The lower room, of stone, and also with a fireplace, is built into the ground and has no interior connection to the room above.

Ramey Sr. died in 1828 and specified in his will "that all my slaves shall be emancipated, at such time as my beloved wife may appoint." He owned 19 slaves, about the number that could be comfortably accommodated in the two Trevor Hill quarters. His widow, Lydia Ramey, died in 1845, but I could find no record of whether she ever freed her husband's slaves.

When Sanford and Lydia's son first appears in the 1850 censuses, he owned 30 slaves, unusual for the Waterford area, where most farmers were Quakers and did not own slaves. Fifteen to 22 slaves lived at Trevor Hill then. Ramey probably rented the others out or they worked on other Ramey properties.

Besides being a farmer, Ramey Jr. practiced law and was a member of the House of Delegates from 1839 to 1845. In 1860, Ramey owned 62 slaves -- in Loudoun, only Elizabeth Carter of Oatlands owned more, 128 -- many of whom he either rented out or bought as an investment with an intent to sell. Conservatively, in 1860 his slaves were worth $20,000, as much or more money than an average Virginia farmer earned in a lifetime of labor.

Ramey and his wife Anna sold Trevor Hill to Charles Fenton Fadeley* in November 1863 for 70,000 Confederate dollars, then worth about 10 cents on the dollar. When Ramey died in September 1865, three months after the Civil War ended, his slaves were free and his Confederate dollars worthless. Sales of his possessions brought a humbling $520.42. His widow purchased a bedstead and scales worth $6.25.

About 1950, Fadeley's great grandson, who shared his name, restored the slave quarters and they became guest quarters. They remain in another family's ownership, and in fine condition.

* Charles Fenton Fadeley was the owner of the stage coach that ran from Winchester through Leesburg to Washington, D.C. during the time he purchased Trevor Hill e.g. Rosemont. He ultimately gave Rosemont to his son as a wedding presant ( his son's name was Charles William Fadeley).

Copyright © Eugene Scheel