Iron Mining in Loudoun County

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Virginia Iron in the Colonial Era![]()

Catoctin Furnace at Cunningham Falls State Park![]()

In the autumn of 1795, the mining of iron began in Loudoun County, on Catoctin Mountain. A boom industry had dawned, one that would not stop until the Civil War, by which point the county had become Virginia's second-biggest producer of iron.

Even in the midst of a depression, in 1860 the recorded output was 2,250 tons valued at $58,000 -- about $1.2 million today.

When mining began on Catoctin Mountain, across the Potomac River from Point of Rocks, Md., the Virginia Piedmont was being transformed from a wilderness into a prosperous agricultural society. Iron farm implements and wagon-wheel rims were replacing wooden ones. The earliest settlers' homes were decaying, and larger new domiciles needed nails and hardware.

An industrial revolution had taken hold, and it was fed by iron.

The deposits in north-central Loudoun were in the middle of a 120-mile mineral belt extending from an area just west of Baltimore to Frostburg, Md.

The first to exploit this iron-laden area were four men named Johnson. At least three were brothers. One, Thomas Johnson, had been Maryland's first governor and was on the U.S. Supreme Court when he became a partner in Josias Clapham & Co., a consortium made up of Clapham and the four Johnsons.

They had purchased 1,310 Loudoun acres in January 1792, at about $10 an acre -- half the going price of local arable land. Clapham, an astute businessman, lived close by at Chestnut Hill, a still-standing manor house. He had represented Loudoun in most of the Revolutionary War conventions, and had been the county's General Assembly delegate from 1770 to 1788. He was also a director of the Patowmack Canal, which, when finished, was to transport iron ingots to Georgetown and Alexandria seaports.

Another incentive toward creating a county iron industry came in 1794, when Congress authorized the building of federal armories to manufacture firearms. Armories needed iron. At the insistence of President George Washington, an armory was located at Harper's Ferry, at Loudoun County's northwest edge, a few hours' journey by wagon from the Catoctin Mountain iron deposits.

To separate iron from its ore, charcoal provided the heat. Dotting the treed hillsides of Catoctin Mountain were charcoal hearths. In these small ovens, hardwood was partially burned to transform it into charcoal. This light residue was then loaded into sacks and then onto mules, and via "charcoal paths" the docile carriers transported their loads down the slopes to stone-and-brick blast furnaces, where the iron ore was smelted.

The refining operation needed a steady flow of water, both to ensure the furnaces wouldn't overheat and to operate bellows that would blow air through the charcoal bed. That water came from nearby Catoctin Creek.

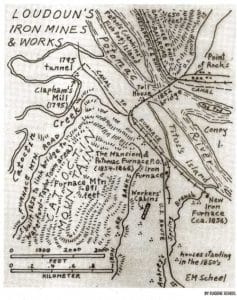

Near the Potomac, the creek bed looped (see map), and in late winter 1795, Clapham & Co. began digging a tunnel through the loop's isthmus, "500 feet through the rock and 60 feet below the surface of the hill," wrote Yardley Taylor in Joseph Martin's 1835 "Gazetteer of Virginia." As the tunnel's upstream mouth was 15 feet higher than its outlet, the rush of water fed a canal that led to the furnaces. In times of low water, a mill pumped water into the tunnel.

The tunnel openings are no longer visible: About 85 years ago, Sam Fawley closed the ends so his cattle wouldn't wander through during dry times.

An 1808 deed describing the property mentioned "Mills and other improvements since erected on the said Land," and "huts [log cabins] and sheds for the accommodation of hands and horses." This complex, which the deed named Potomac Furnace, was the beginning of today's village of Furnace Mountain.

Taylor provided one of the first local descriptions of the furnace area, in Martin's "Gazetteer": "A furnace formerly existed at the E[ast] base of Kittoctan mountain, on the margin of the Potomac river, but has been out of blast for a good many years owing to the scarcity of fuel." The furnace property's hardwoods had evidently been depleted.

Taylor also supplied the next account of the area, in an 1853 pamphlet. He wrote: "A furnace has been erected here a few years ago, and it has been in blast part of the time with varied success."

The new furnace was placed into blast about 1848 by Frank Moorman, a German who was educated in the iron trade in Holland.

In 1852 the first Point of Rocks bridge opened, and on its wooden planking a double-track narrow-gauge railroad from Loudoun connected with the main line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad at Point of Rocks. Since wagons and horses used the bridge too, only one one-way mule-drawn train was permitted on it at a time.

Besides loading the refined ore from mule trains onto B&O hoppers, the return trips brought coke to fuel the furnaces. Coke produced a hotter fire than did charcoal.

Coke, the bridge, the railroad -- these amenities induced Pennsylvania investor John W. Geary, the former mayor of San Francisco, and Baltimore businessman Michael P. O'Kern to hire experts to evaluate the Catoctin Mountain furnace tract. Geary and O'Kern were thinking of buying it, even though Geary was far away, having been appointed governor of the new Kansas Territory.

G. Jenkin Phillips, a geologist, examined the property, and reported to Geary in 1856: "The indications of ore are very great upon the surface; large blocks lie promiscuously upon the top of the ground, and nearly everywhere the surface itself would make iron."

James Higgins, the state agricultural chemist of Maryland, estimated 1.2 million tons had been removed from the mine in its 60 years. He wrote Geary that same year: "At the Potomac river there is an opening which exposes the bed of ore in almost one continuous mass, extending from a few feet from the surface to depths yet not ascertained." Higgins also mentioned that other sections of the tract contained "immense quantities, being either found in small masses, closely compacted and easily taken out with the pick, or in large blocks with many tons weight."

Another account, though, might better explain the comments of Phillips and Higgins: Thomas Johnson's grandson, Andrew Moorman, whose father was ironmaster Frank Moorman, was interviewed by area historian Briscoe Goodhart for the Loudoun Mirror newspaper in the early 1900s.

"New prospective purchasers were expected to come with a view of purchase. A large force was put to work getting out ore exposed to view and in great abundance as the new purchasers approached," Goodhart quoted Moorman as saying. "The fuse was lighted and great quantities of ore were thrown into the air and scattered promiscuously around . . . giving the property an appearance of an Eldorado, a land of plenty."

Geary and O'Kern bought the furnace tract, now 626 acres, for a record Loudoun price of $100,000.

Goodhart noted in the Mirror that after the purchase, a new ironmaster, Howard James, "a gentleman but with one arm, but that was as good as two arms of some men, immediately began erection of a new furnace . . . to be double the capacity of the present plant."

In addition, James had a large boarding house built to supplement some 25 workers' hovels. The domicile, sometimes called "The Mansion" and sometimes called "The Shanty," also housed a post office named Potomac Furnace from 1854 to 1866.

For a few months in 1856 and early 1857, the furnace tract prospered, but then James died of a fever and the depression of 1857 stalled purchases of iron. Geary found himself in debt to the tune of $41,500 later that year. His creditors, however, took him off the hook by buying his allotment for a dollar and 10,000 shares of capital stock in the Potomac Iron Co. -- the enterprise's final corporate name.

Geary would next enter Virginia as commander of the Union forces who first occupied Loudoun in February and March 1862 and then marched through Fauquier that spring.

James's new iron furnace lingered in its old location, by the Potomac and right bank of Awbrey's Spring Branch, until about 1870, when Addison McKimmey moved it to Saint Clair Lane, north of Lucketts. McKimmey then converted the furnace into a still-standing three-hole lime kiln.

The Mansion burned, the log huts decayed, and about all that was plainly visible of the furnace tract when I first saw it some 40 years ago were open pits, strewn with iron deposits, on the east side of Route 15 by Awbrey's Spring Branch. The pits had been known as "John Steele's caves": Lucille Green Athey told me that Steele, a hermit, built a three-room hovel in a pit.

Once he got very sick, Athey said, and Minerva McGavack, a neighbor who lived in one of the log huts, took him out of the pit and nursed him back to health. Then Steele went back to the pit.

The pits have been leveled out. Built upon the spot are expensive homes.

For further reading: A Celebration of Iron: A History, 1609-1892, by Stanley K. Dickinson (Baltimore: Gateway Press, 2003).

Copyright 2005 © Eugene Scheel