The Carolina Road

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Wickepedia - The Carolina Road »

In Colonial Loudoun and Fauquier counties, the most important travelway was the main north-to-south road. This bed of dirt, no more than 10 feet wide, was called the Carolina Road, for its southern terminus was an Indian trading post on Occaneechie Island in the Roanoke River, on the Virginia-Carolina' border.

The road was favored by Colonists – as it had been favored by their predecessors, the Algonquin and Iroquois Indians – because of numerous springs along its route, milder temperatures east of the mountains and relatively safe fords across major rivers and streams.

In Loudoun and Prince William counties, the Carolina Road follows or parallels U.S. Route 15, the James Monroe and James Madison highway. In Fauquier, it follows several secondary roads east of Routes 15-29.

One can still drive on 55 of the road's 65 miles through the three counties, across a region described by Scenic America, an environmental advocacy group, as "a small piece of the American landscape permeated with the history and culture of the American nation." The group calls a trip along this corridor “The Journey Through Hallowed Ground."

In Colonial times, the journey began in spring, when thawed ground had dried a bit, rivers and streams had lowered and the road had been "grubbed up" – the annoying growth cut and the roadbed smoothed, a task mandated by the county court and performed by residents along the road.

'The road's northern terminus was Frederick, Md., an important Colonial town with feeder roads from Pennsylvania. Thomas Scharf, Western Maryland's premier chronicler, picked 1740 as the date for the road's beginnings.

Writing in 1882, he noted: “The goods sent from Frederick were boots and shoes, saddles and harness, woolen goods, linen and woolen and flax seed threads. They were carried on pack horses and were exchanged [in Virginia and North Carolina] for cotton, indigo, and money." The carriers, according to Scharf, were "thrifty Germans."

In 1742, the Virginia General Assembly describes the travelers as “drivers vagrant people peddling and selling horses; and either buy or steal a great number of cattle which in their return they drive through the frontier counties; and often take away with them the cattle of the inhabitants under pretence that they cannot separate them from their own droves."

Indeed, as early as 1747, a Fauquier land grant refers to the Carolina Road as "Rogues Road," a name that appears in Fauquier and Loudoun deeds throughout the early 19OOs. A few miles north of Leesburg, on old Montresor farm, a narrow wooded stream valley still bears the name Rogues' Hollow, for tradition states that this geographic depression was the lair for thieves about to plunder travelers.

Writings of the journeymen themselves abound in Picaresque color. Elkanah Watson, a Continental Army courier, noted in 1777 that after crossing the Potomac River at "Newland's [Noland's] Ferry," which linked the Maryland and Loudoun stretches of the Carolina Road, he was served dinner "by half-naked savages" at the home of Josiah Clapham, Loudoun's General Assembly representative.

The repast led Watson to describe the county as "a wilderness region infested by a semi-barbarian population."

Watson was particularly concerned, for sewn into his clothes was $50,000 in paper currency (more than $1 million today), the payroll for Continental troops in the South.

Two years later, Lt. Thomas Anburey, of Gen. John Burgoyne's British and Hessian armies, who had been captured at the Battle of Saratoga, reached Noland's Ferry on the forced January trek to a prisoner of war camp near Charlottesville.

He wrote: "We crossed the Potowmack River with imminent danger as the' current was very rapid. The scowe at one time was quite fastened in the ice. On our entering Virginia the roads were exceedingly bad from the late fall of snow which was encrusted, but not sufficiently to bear the weight of a man, so we were continually sinking up to our knees and culling our shins and ancles."

Baroness Fredericka von Massow also was captured but journeyed by wagon with her children and servants on horseback, who rode ahead to clear the way. Passing through Loudoun south of Leesburg, she remarked on the country's being "picturesque" but "by reason of its wildness, inspired us with terror. Often we were in danger of our lives while going along these break-neck roads."

Moravian Bishop John Frederick Reichel chose nay as his travel month along the Carolina Road when he and his party set out from Bethlehem, Pa., to Salem, N.C., in 1780.

At Noland's Ferry, his diary records that the group was robbed, adding that "this neighborhood is far-famed for robbery and theft."

When they stopped that evening, two miles north of Leesburg by Big Spring, some of their horses strayed, and as they were rounding them up, their camp was again plundered, "by negroes who had a free evening and were roaming everywhere."

Reichel's diary also gives the first descriptions of the Carolina Road in lower Fauquier – "hilly, rough and marshy," adding that at the "Rappihannik" River, "there is neither bridge nor ferry." On the party's return trip that October, lower Fauquier's route is referred to as "a very bad stony road, especially in the place known as Devil's Race Ground, where we saw rock enough".

Johann David Schoepf, a German surgeon, wrote kinder words of the Carolina Road in lower Fauquier in 1783, describing it as "a great broad road" bordered by "so much waste or new cleared land." He added that the owners have "great and extensive tracts of which they will sell none so as to leave their families the more. All of them let land in parcels . . . worked and settled by tenants.”

Schoepf also leaves us the first description of a tavern along the road. Taverns were then called ordinaries, from the French word ordinnire, referring to their fixed-price meals.

An unnamed Leesburg tavern was "easily identified by the great number of miscellaneous papers and advertisements with which the walls and doors are plaistered. . . In this way the traveler is afforded a many sided entertainment and can inform himself as to where the taxes are heavy, where wives have run away, horses have been stolen, or the new Doctor has settled. . . .

“These ordinaries are commodious enough when there are not too many guests, but coffee, ham and eggs are commonly the sole entertainment. Ham is the great delicacy to the Virginian."

As horseback travel was reckoned at 4 mph, an ordinary's location was gauged to travel times between meals. There were usually two or three ordinaries in Leesburg, and moving south, William West's a mile south of today's Gilbert's Comer, the Red House at Haymarket, then George Neavill's at Auburn and Landon Carter's at Norman's Ford on the Rappahannock River.

Leesburg, the one major town along the Carolina Road, was pictured in less-than-alluring words. In 1774, diarist Nicholas Cresswell noted that it was "very indifferently built" and had "few inhabitants and little trade."

In 1781, Capt. John Davis, of the Continental Army, made a reference to "Leesburg, the appearance of which I was very much disappointed in." And in 1783, Schoepf called the town "a Place of few and insignificant wooden houses."

While Leesburg began to prosper as a result of the wealthy farm country around it and because it was "very advantageously situated," as Cresswell put it, the Carolina Road began to lose importance after the rise of Washington, the new federal city, in the 1790s.

Improvements to the King's Highway, called the Post Road as it was the major mail route between Boston, Washington and Richmond, also beckoned north-south travelers farther east. Bridges began to span the tidewater stretches of the Potomac and Rappahannock, and by the 1850s, telegraph poles and wires linking north and south lined the Post Road, soon to be called Telegraph Road, today's U.S. Route 1.

In Loudoun, a new parallel travelway bypassed the Carolina Road. A bridge built at Point of Rocks in 1850 proved safer than Noland's Ferry, though the ferry continued operating unti1 1920. A new toll road, the present Route 15 was built in 1875 and straightened the route between Leesburg and today’s Gilbert’s Corner at the present Route 50, although Route 15 south of Gilbert's Corner was not cut through unti1 1941.

In Fauquier, the way south shifted west with completion of the Warrenton-to-Alexandria Turnpike in 1825 and construction of a turnpike from Warrenton to Waterloo, open by 1850. An extension of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad through lower Fauquier to today's Remington in 1852 bypassed Norman's Ford, and the growth of Remington ended that ford's prominence.

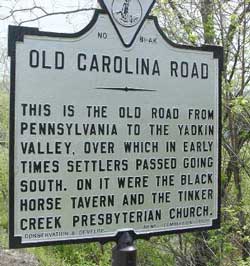

Similar shifts of travel patterns through Virginia gave rise to a mid-19th century prefix that now graces road signs and historical markers: Old Carolina Road- "old" in history, "new" in that its corridor still separates urban development on its east from the rural Piedmont Virginia on the west.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel